Back in March, as COVID-19 forced a nationwide lockdown, non-residential reentry centers operated by GEO Reentry Services were moving quickly to adapt their programming so participants could continue receiving evidence-based treatment and reentry services.

Many of these facilities offer good examples of intelligent service modifications that allowed participants to not only continue working toward their treatment goals, but to receive personal support as they did so.

During lockdown, the Monterey County Day Reporting Center was one of many GEO Reentry centers that offered participants remote treatment while its doors were closed. Staff provided daily check-ins, group meetings through videoconferencing, treatment plan work and substance abuse services over the telephone, as well as one-on-one phone meetings with participants’ assigned case managers.

Staff at the Fresno County Day Reporting Center made daily check-in phone calls to keep participants accountable and delivered treatment services via one-on-one calls, group teleconferences and online-based platforms. The results were encouraging; with 16 participants enrolled in April and May, the center’s Engagement and Accountability Check-In rate came out at an impressive 74%.

Throughout the shutdown, the Neptune Community Resource Center in New Jersey operated as a reporting site where local parolees with limited means of travel could see their parole officers locally. The center also invited providers from community organizations to come in during these times so that participants could access much-needed services.

Many of the centers also took immediate action to make sure participants and their families felt personally supported during this difficult time, as many Americans dealt with lack of income due to job loss, unstable housing situations, problems paying for food and in some, cases, the illness itself.

The Covington Day Reporting Center in Louisiana created care packages using donations from the local Target store, which were then dropped off on participants’ porches and doorsteps by staff wearing personal protective equipment to comply with the CDC-recommended social distancing policy.

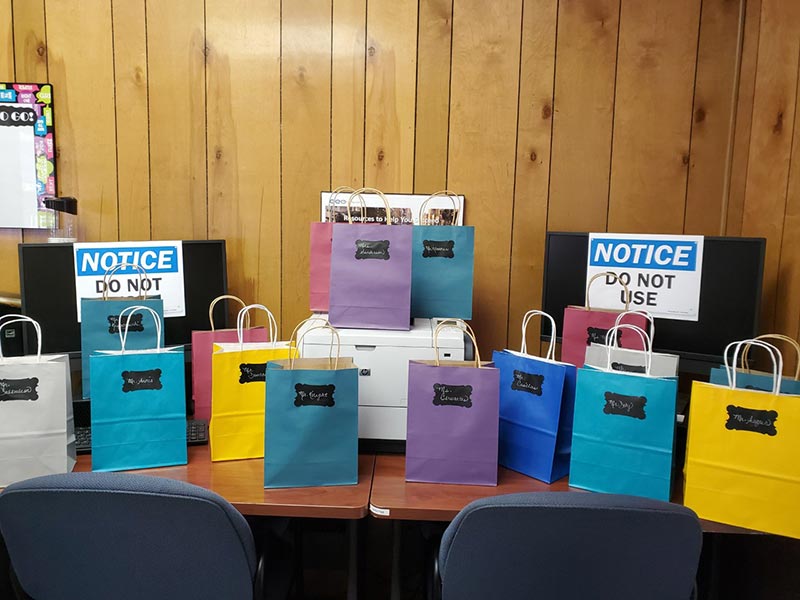

Staff at the Mendocino County Day Reporting Center developed a “Build-a-Bag” incentive program to reward participants for their dedication to the program despite logistical difficulties during COVID-19. Each time participants checked in, attended a group meeting, took part in ICBT or completed group work, a staff member would place a small, fun item, like sunscreen, stress balls, candy or Gatorade, into that participant’s designated bag.

At the Baton Rouge Day Reporting Center in Louisiana, case managers reached out to felon-friendly businesses every day to find out about new opportunities, submitted job applications on behalf of less computer-literate participants; arranged pick-up for items donated to participants; and mailed GED and jobs materials and information on community resources to participants’ homes.

Some centers also used the lockdown for staff retraining. When the Ventura County Adult Reporting and Resource Center was closed to participants, staff members had the chance to reinforce important skills and develop new ones through weekly webinars and multiple in-house trainings, which focused on Evidence-Based Practices, Motivational Interviewing, Pro-social Modeling, Substance Abuse intervention Cross-Training and more.

Now, as stay-at-home orders ease, many GEO Reentry centers are implementing a phased approach for increasing in-person services. Facilities like the Vineland Community Resource Center in New Jersey have made numerous physical changes to ensure staff and participants’ safety, including affixing yellow Xs to the floors and modifying group rooms to ensure six-feet social distancing. Large plastic guards have been added to desks for use during individual sessions and meetings, and staff have created and hung educational signs with information about preventing COVID-19.

During the lockdown, GEO Reentry non-residential reentry centers nationwide served as essential service providers for participants, a vulnerable population to begin with but especially in a pandemic. At the same time, these centers’ ability to continue their services uninterrupted have helped supervising parole and probation officers with their caseloads and in their efforts to reduce the risk of recidivism.